Tony Kriletich, a Northern California radiology technologist, said he never missed one day of work in 14 years. That changed Sept. 19.

Last summer, Kriletich, 65, a marathoner and triathlete, was concerned when routine activities, like working in his garden, were leaving him breathless. His wife, Patricia, also noticed he was unusually fatigued. She recalls one stretch of days where he was struggling to catch his breath.

Tony Kriletich was a marathoner and triathlete who knew something was off when routine activities left him short of breath.

“I said to Tony, let’s go to the emergency room and have them check you out, but he fought me on it,” she said. “Men can be stubborn like that.”

Kriletich says, “It didn’t make any sense because the rest of my body was willing to work.”

Believing his episodes were signs of aging or maybe something else going on, Kriletich waited for an annual physical to share his symptoms.

“COVID precautions meant that regular medical appointments were being done virtually,” he said, “so I waited until my in-person appointment.”

Once in the office, his primary care provider heard something alarming: Kriletich’s heart was beating out of rhythm and he would need to go to the emergency department right away. Fortunately, that distance was only as far as walking across the parking lot to his workplace: Novato Community Hospital in Marin County.

“I had sandals on,” he said. “I wasn’t thinking I was going into the hospital for a weeks-long journey.”

Haywire Heartbeat

On Sept. 19, Kriletich was admitted to Novato Community Hospital with what doctors believed was atrial fibrillation (AFib). From there, doctors at another local hospital performed an angiogram. Kriletich’s test came back “clean,” but doctors still could not control his heart’s rhythm. He was transferred to Sutter’s Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, where staff have the capabilities to perform more specific studies of the heart and electrophysiology. Unfortunately, Kriletich failed each test and was sent to Sutter’s California Pacific Medical Center (CPMC) Van Ness Campus in San Francisco.

Tony Kriletich was admitted to the hospital. Here he shows off all the monitors he was hooked up to.

Kriletich’s care team at CPMC, led by Michael Pham, M.D., conducted a series of tests to determine why his heart rhythm could not be controlled. After a four-day exhaustive investigation came a diagnosis: sarcoidosis (the main culprit), plus AFib.

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a rare disease in which clusters of white blood cells, called granulomas, form in the tissue of the heart. While any part of the heart can be affected, cell clusters most often form in the heart muscle where they can interfere with the heart’s electrical system and cause irregular heartbeats, or arrhythmias. If untreated, cardiac sarcoidosis can result in heart failure.

Kriletich was added to the national heart transplant registry on Oct. 5. To keep him going, his doctors inserted a mechanical device called a balloon pump, which kept Kriletich’s heart beating at a regular rhythm.

“For the first part of me being in the hospital, and because of COVID restrictions, I didn’t have visitors,” Kriletich said. “Even though that was hard on my family, it was almost better because I was truly immobile. With the balloon pump, doctors go through the femoral artery in your leg and you must lay perfectly flat. You can’t bend at the waist because they don’t want it kinking.”

New Heart in Four Days

On the evening of Oct. 8, Kriletich’s doctors shared the miraculous news that a heart had been found and he would have his operation the next day. He underwent his transplant at CPMC Van Ness Campus, just two floors down from his patient room.

With a heart transplant comes a load of medications to keep track of.

“It was a real fast experience,” Kriletich said. “I don’t know how I was blessed with only four days, and I know that’s not typical.”

Kriletich’s transplant surgeon, Brett Sheridan, M.D., remarked that “undergoing a heart transplant is like pulling out the engine of a car and putting a new one in.”

Kriletich stayed in the hospital for two weeks after his operation.

“The dedication, knowledge and the willingness to ‘get this done’ speaks volumes about the quality of this transplant team,” Kriletich said. “I am very humbled by it.”

Heart Transplant No. 524

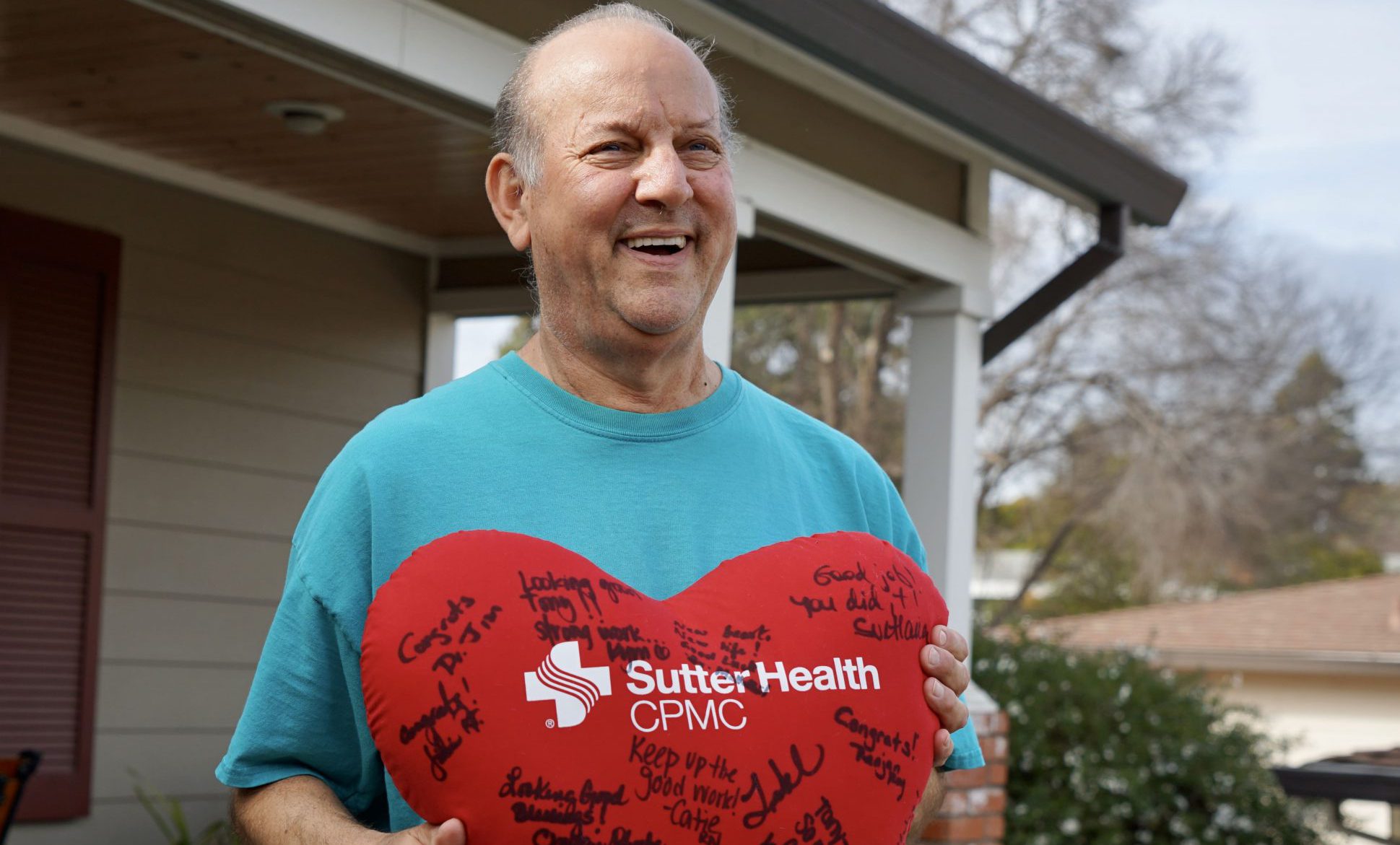

Months later, Kriletich’s strength continues to grow, and he learned he was CPMC’s 524th heart transplant. “I love my coworkers and the support from Sutter; it’s just been incredible,” said Kriletich.

The back side of the heart pillow Tony Kriletich has more well wishes.

“Tony is a model patient,” said Dr. Pham. “Because he’s a healthcare provider and medical professional, he understands what’s happening and he’s had smooth course after the transplant.”

Kriletich plans to celebrate the one-year anniversary of his transplant with a 29-mile walk from Novato, across the Golden Gate Bridge to CPMC.

“The long-distance walk he’s planning is a testament to Kriletich’s endurance,” said Dr. Pham. “He can do anything, it’s just a matter of training.”