Donating blood probably isn’t on your summer bucket list — but maybe it should be, say lab technicians at Sutter’s California Pacific Medical Center’s blood bank in San Francisco. Summertime, while a high point of the year for fun, travel and get-togethers, is a low point for blood donations. This seasonal slump matters, particularly for trauma centers and acute care hospitals that rely on robust supplies of blood to help treat and care for patients.

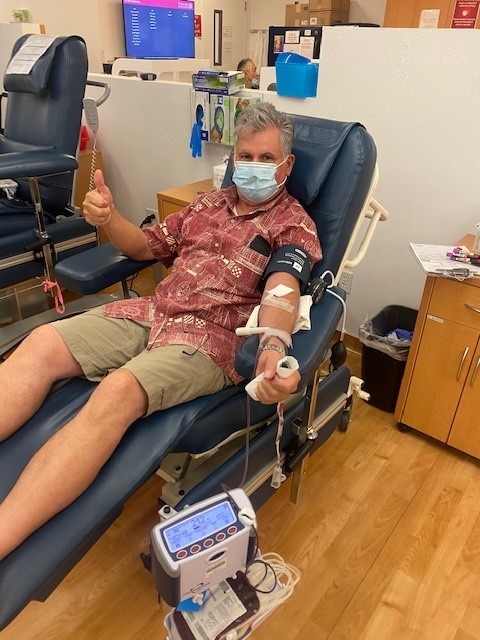

Mark Lindberg gets his blood drawn at a blood donation center near his home in Mountain View, Calif.

So, if you’re lounging by the pool and daydreaming about your next summer adventure, consider using your extra downtime to give blood. It could be the start of a lifelong relationship of blood donation, much like perennial giver Mark Lindberg.

The Mountain View resident first rolled up his sleeve to give blood in the 1970s at the suggestion of a friend, and he’s been giving faithfully ever since. Forty years later and Lindberg estimates he’s donated at least 17 gallons of his O-positive blood, typically signing up three to five times a year.

“You can give every 56 days, but it can be tricky to maximize the calendar,” Lindberg says. He expects to reach his 80th visit this year at the blood donation center near his home.

Sign up to donate blood here. You can also find upcoming blood drives hosted by The American Red Cross here.

Donations Keep Hospital Blood Supply Flowing

Blood banks, or more formally known as Transfusion Service, are the lifelines of hospitals. Ironically, they are staffed by skilled technicians who never see patients’ faces or have the need to venture onto patient floors. Their work takes place under the bright lights of the laboratory using pipettes, vials, microscopes, high-speed centrifuges and other critical diagnostic instrumentation.

Benidict “Ben” Blando, a clinical laboratory scientist, prepares to perform a blood test at the CPMC Van Ness campus blood bank in San Francisco.

“Everyone thinks of us as these vampires taking people’s blood, but we’re actually highly trained and licensed clinical laboratory scientists,” says Simon Dunn, a director of laboratory and pathology at Sutter Health. Dunn oversees blood bank operations at all three of CPMC’s acute care hospital campuses in San Francisco.

As both an acute care facility and the region’s tertiary referral center, CPMC uses significant amounts of blood and blood products, which are plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets.

So, while someone in Dunn’s role has never met a donor like Mark Lindberg in person, he says it’s entirely possible that Lindberg’s blood has been routed through one of CPMC’s laboratories many times over to patients in need.

“Because blood products are typically separated into many components [including plasma and platelets], a person like Mark can feel good knowing they have directly helped someone whether they came in for a trauma, cancer care, a transplant operation or some other malady where a blood transfusion was required,” says Dunn.

To paint the picture of a bustling blood bank, Dunn focuses on CPMC’s newest and largest campus, Van Ness, which uses 1,000 or more units of blood products each month. This is on the high side, he explains, but that makes sense when you understand the hospital’s standing as a hub for advanced organ therapies and transplantation services. The medical facility also has a very active labor and delivery population. In CPMC’s neonatal intensive care unit, for instance, even the tiniest newborns may need a whole blood transfusion.

Other procedures like liver transplants are such that unusually large quantities of blood are used at once. Care teams at CPMC will work in advance with the patient’s surgical team to ensure enough units of compatible blood are prepped and ready to go, with even more units of blood on standby. Dunn says a liver transplant can require as many as 30 units of blood. In some infrequent cases, he says it is not unheard of to go through as many as 100 units of blood during a single liver transplant operation, an occurrence that typically happens only a few times a year. For this reason, lab technicians must keep a close eye on blood supply at all times, particularly for units of the universally given O-negative blood.

“The blood supply is very important for our program to serve our patients,” says Dunn. He estimates about 70%-80% of critical diagnostic information is generated from the laboratory and is what doctors use to inform decisions about patient care.

CPMC Transfusion Service Supervisor Susan Lee prepares units of blood for transport.

One technology that keeps things efficient across all of Sutter’s blood banks is its single electronic health record (EHR). CPMC, like other hospital affiliates across Sutter Health’s integrated network, share an EHR. This powerful tool helps ensure patient information is readily available and can travel with them digitally in case they are transferred to another Sutter facility.

“That’s the advantage of having an EHR that’s shared across the system,” says Dunn. “If a patient from Sacramento comes to CPMC for a transplant, once we get into their medical record, we can see their blood type and if they have antibodies or not.” Dunn says they will still sample the patient’s blood and perform a test called a “cross-match” but it gives a baseline of understanding.

Blood supply is also standardized across Sutter, including using the same supplier Vitalant. “We all use the same products and sometimes we share inventory, especially within region,” says Dunn. In a hospital like CPMC’s Van Ness campus, blood inventory can turn over very fast. Lab staff can phone another hospital in the Sutter system, such as nearby Mills-Peninsula Medical Center in Burlingame, and request extra units.

According to the World Health Organization’s website, “Ensuring access of all patients who require transfusion to safe, effective and quality-assured blood products is a key component of an effective health system and vital for patient safety.”

Susan Lee shows pulls out various blood products from the the CPMC lab’s large storage freezers.

Staff Step Up to Give, But More Like Mark Are Needed

CPMC and other Sutter hospitals routinely hosts staff blood drives. On average, each quarterly drive brings in about 40 units of blood. While every pint helps, it still leaves a sizeable gap in what’s needed for patients. This is why giving blood and community blood donation events are so crucial.

“It’s not as if we have endless supplies of blood sitting on a shelf like you’d find [items] at Safeway,” says Susan Lee, a supervisor in CPMC’s Van Ness campus blood bank. “Blood has to be donated.”

Nationally, more than 4.5 million Americans require a blood transfusion annually, and despite this extensive need, only about 10% of eligible blood donors in the United States actually donate.

The U.S. also currently finds itself in midst of its worst blood shortage in a decade. According to the Red Cross, blood donations are down 10% since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. High school and college donations are down even more drastically—a staggering 62%—within an age group that typically provides a quarter of blood donations a year.

This summer, consider making a date to donate blood. It’s an altruistic activity that has a true life-saving benefit.

Or just ask Mark Lindberg, who says, “It makes me feel good to be giving something so important that I’ve made it a priority. I also enjoy the passo-orange-guava drink and oatmeal cookie that I get afterward.”