Growing up in a Latino working-class environment, Eric Arauza worked toward a life similar to those in his community: working a labor job in areas such as construction or food services. After all, his father, Candelario, Sr., is a truck driver, and together with Arauza’s mother, Ana Lisa, they operate a Mexican taco catering business.

But the culmination of Arauza’s own experiences plus those of his family, friends and neighbors living in the Broderick neighborhood of West Sacramento, Calif., led him down another path. He saw generations of his family diagnosed with diabetes, going to a community health clinic for care, having to wait several months for an appointment, waking up at 6 a.m. to catch a bus knowing any one of them could be turned away if the clinic didn’t have the staff or resources that day to see patients.

“Those were the initial drivers that made me feel this is not fair, and it didn’t make sense as I grew up seeing my family not able to afford medications … having to choose this or that, and having to prioritize basic living expenses over their health,” he says.

Arauza’s goal is to break the cycle where positive health outcomes are often reserved for those from higher-income ZIP codes. And he plans on doing so by becoming the first physician in his family. He is now attending Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science with a full-tuition scholarship, academic support and experiential learning opportunities made possible through California-based Sutter Health, a not-for-profit, integrated health system.

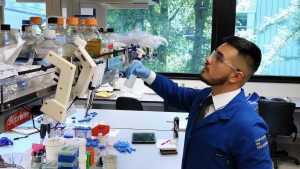

Eric Arauza conducting research at University at California, Davis.

Arauza credits exposure to programs in middle and high school, as well as those early in his college career, as his first opportunities to stretch his boundaries and dreams. He was part of the Advancement Via Individual Determination, or AVID, program from 6th-12th grade, which helps prepare students for college eligibility. Arauza also joined ACE, otherwise known as the Academic Excellence Program, while attending the University of California, Santa Cruz. ACE is dedicated to advancing educational equity through peer mentoring, skill-building and community development.

Arauza recalls an ACE program mentor who once handed him a large stack of fliers that outlined numerous pre-health programs, scholarships and grants for him to explore and pursue. It loomed large and only seemed to grow as Arauza’s old doubts took hold of him.

“I was telling him, ‘I can’t do this. I come from a community where we don’t usually become doctors. Is this really a space for me?’”

Eric Arauza during a rotation with Prep Medico.

His mentor urged him on, telling him these were opportunities designed for first-generation students just like him, with lots of financial and career mentorship to offer. That moment set Arauza on a path of voracious self-discovery. He participated in numerous competitive internships, including Prep Medico, Health Career Connections and AltaMed Scholars. They helped him build the confidence and skills he needed.

“For me, it gave me reassurance that I am who my family and friends have told me: ‘the person people are waiting for.’ That feeling gives me validity and strong motivation.”

Arauza will soon join the 6% of Latino physicians in California. He says he chose Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science because it is a school built on social justice, health equity and advancing medicine for all.

“I really felt connected to Charles Drew. The faculty and the students felt like home. It felt like hanging out with my friends and cousins, and to have that in a place where we will study medicine is unique… To come into one school where all this is, it feels too good to be true.”

Arauza is especially intrigued by the university’s investments in youth, particularly its Saturday Science Academy, which aims to jumpstart student interest in studying science and health education, as well as promote employment in those areas. He says it reminds him of programs he participated in as a kid.

Perhaps it isn’t a surprise that Arauza finds himself drawn to the field of pediatrics. He says kids are naturally ambitious, which to him is a precious resource.

“What I have learned is their environment determines how much of their ambition can turn into a reality,” he said.

Eric Arauza sporting a race car driver outfit while playing in his backyard as a young child.

Arauza reflects on his own childhood and his feelings of ambition. He also remembers the feeling of not knowing how to channel it because the path wasn’t always clear, especially since his neighborhood exposed him to gangs and violence. He says if there isn’t mentorship and pathway programs for youth in those environments, they may feel those dreams aren’t possible.

Arauza is the first to say he doesn’t want to come across to others as preaching they must follow his path to succeed.

“No one will have the same journey into medicine as me. After I graduated college, I worked for five years before applying to medical school. I am not the perfect example,” Arauza said. But what he does want people to know is that it can be done.

When asked what it will feel like when he is officially called “Dr.” for the first time, Arauza pauses and thoughtfully considers his response.

“I know that for patients I am someone they can trust, someone who will hear them out and speak Spanish with,” he said. “And I would probably tell them to call me Eric. My goal as physician is to let them know ‘I am just like you, I have been there or I know someone who has been there.’”